My best days in New York were in the fall of 1987 working hard as an intern at a law firm on what is now Liberty Square close to Wall Street, while living on Abingdon Square, actually 299 West 12th Street, not far from a French restaurant, Florent on Gansevoort Street, which in later years would be my touch base venue to have dinner, at least once, when visiting the city. This time, November 2015, returning after twelve years of absence, the restaurant had disappeared and made way for a neighborhood of fashion and a new riverside Whitney Museum of American Art, a house originally built by Gertrude Vanderbilt for America’s second independence, after the invention of steamships crossing back the Atlantic Ocean, by taking an interest in what her compatriots could do without a stay in Paris, London or the Netherlands.

My invitation to attend an event in New York had not come from the Whitney Museum however, nor were Picasso’s sculptures or Walid Raad’s exhibition in MoMA or Jim Shaw at the New Museum immediate causes to visit the city of tolerance and ambition. What brought me to New York was an invitation from the permanent representative of Saudi Arabia at the United Nations to attend the launch of Our Mother’s House: a many meters long decorative and symbolic wall painting made in the Asir region of Saudi Arabia by twenty or so women under the artistic design and coordination of Fahmi Basrawi, who was kind enough to allow me to capture her with her husband with my iPhone. I could share more pictures of the painting and of the dinner with informative lectures that followed somewhere on 1st Avenue for a modest audience of experts and influencers perhaps, but the image that we also had to deal with that same evening, was the news of a verdict of death for Ashraf Fayadh, a poet in the same Asir region, which called up an impenetrable fog above an otherwise perfectly blue (or be it red) sea.

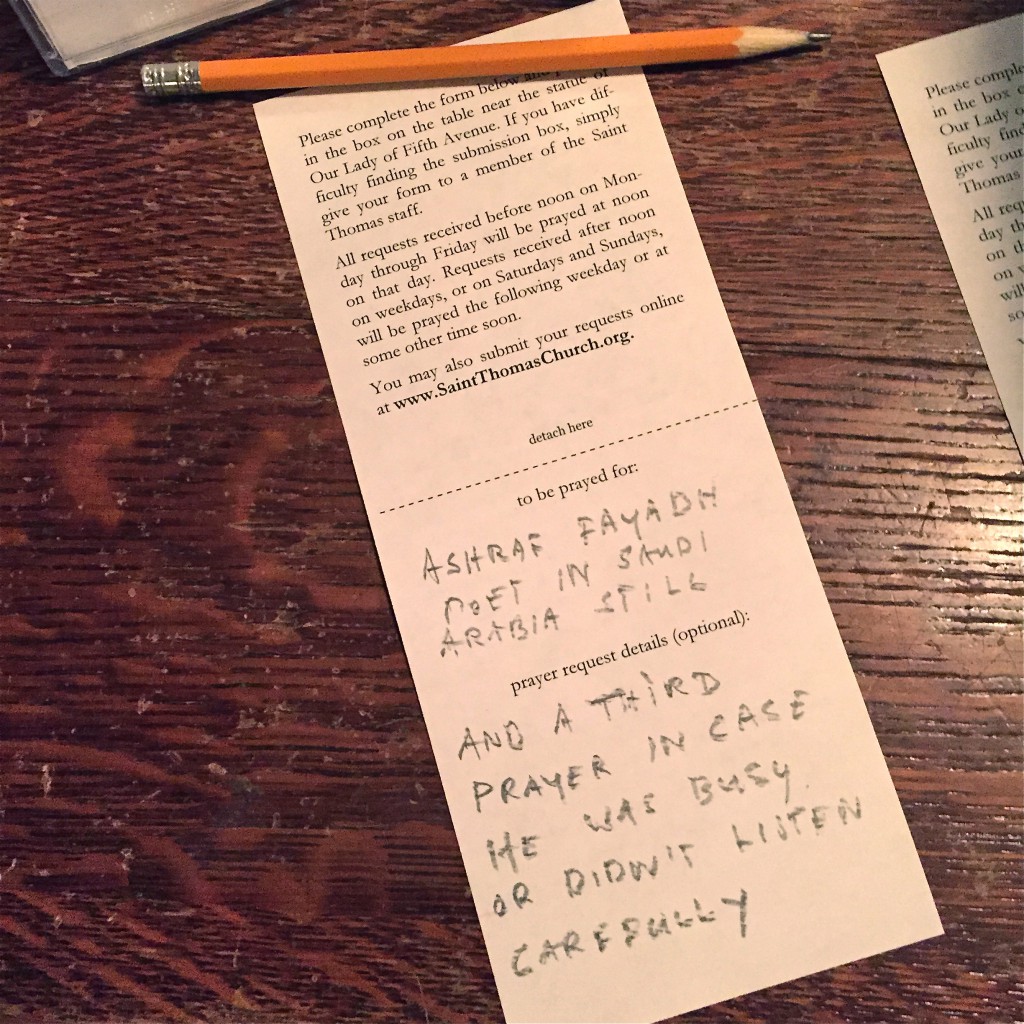

So walking the streets of New York the next day, enjoying how the skyscrapers direct the eyes towards the heavens, and on my way to see Picasso’s sculpture in MoMA, I fell for a short detour and entered this large church, the religious home of many who are ancient and respected in New York, the Saint Thomas Church, and stumbled upon another ‘mother of the house,’ made rather recently by a female artist from England, Concordia Scott, who appears to have spent her life as a nun and artist. Being mostly of the reformed ways of John Calvin the Dutch find statues in a religious setting equally silly and offensive as many if not all Muslims do, however the bronze of Our Lady of Fifth Avenue was charming and then next to it, there was a box. One in which visitors were invited to drop prayer requests for people in need of them. Reprimanding myself for doing something I do not really belief in, filling out paperwork and in the wrong church, I put in three prayer requests. There always seems to be some value in repetition. The picture is of the last request.

MoMA was nearby and Walid Raad shared there with us how to materialize the unseen and ferry truth trough a density of unknowns. Does that make sense? I do not know, but somehow I could breath a bit of fresh air that might permeate in time not only the wall’s of their mother’s houses, but also the air-conditioned terminals and lobbies of the Persian Gulf. I share here this overview of the colors and forms that during the Lebanese civil war, Walid believes, went into hiding in not art, but typography.

On another floor there was the amazing assembly of sculptures made by this animalistic Hercules of a man, Picasso. MoMA made a beautiful exhibition guide with thin and light drawings of only the outlines of the numbered sculptures. Woman, woman, woman, doll and figure, bathers and bull, apple, violin, bottles and glass. Last and not least, a double metamorphosis. Such are the titles and were the light issues on Picasso’s mind, but what is left now are often rocks of eternity. We could easily do without them and for ever miss them.