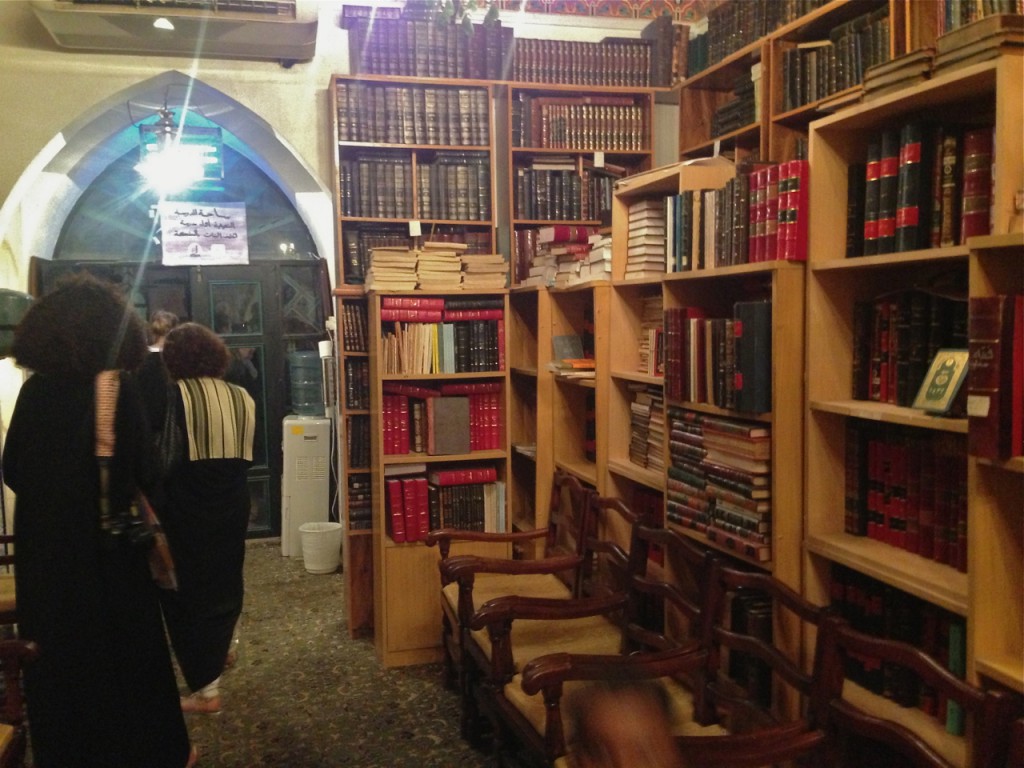

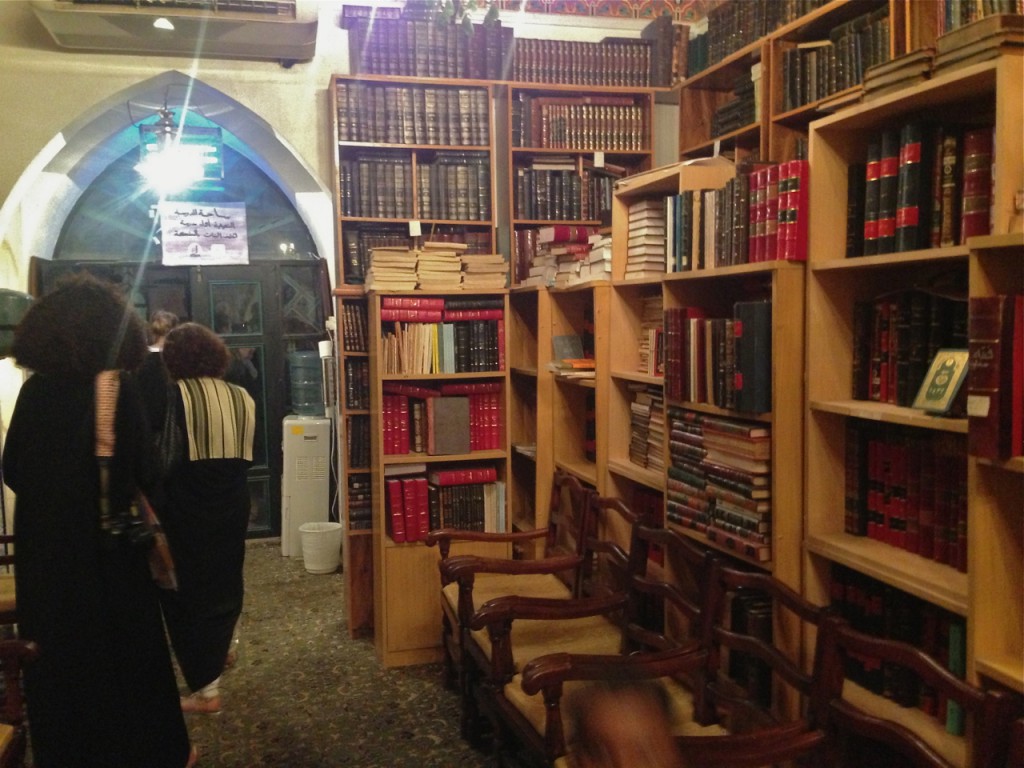

Passing through the law firm of Abdul Rahman O. Nassief in Jeddah.

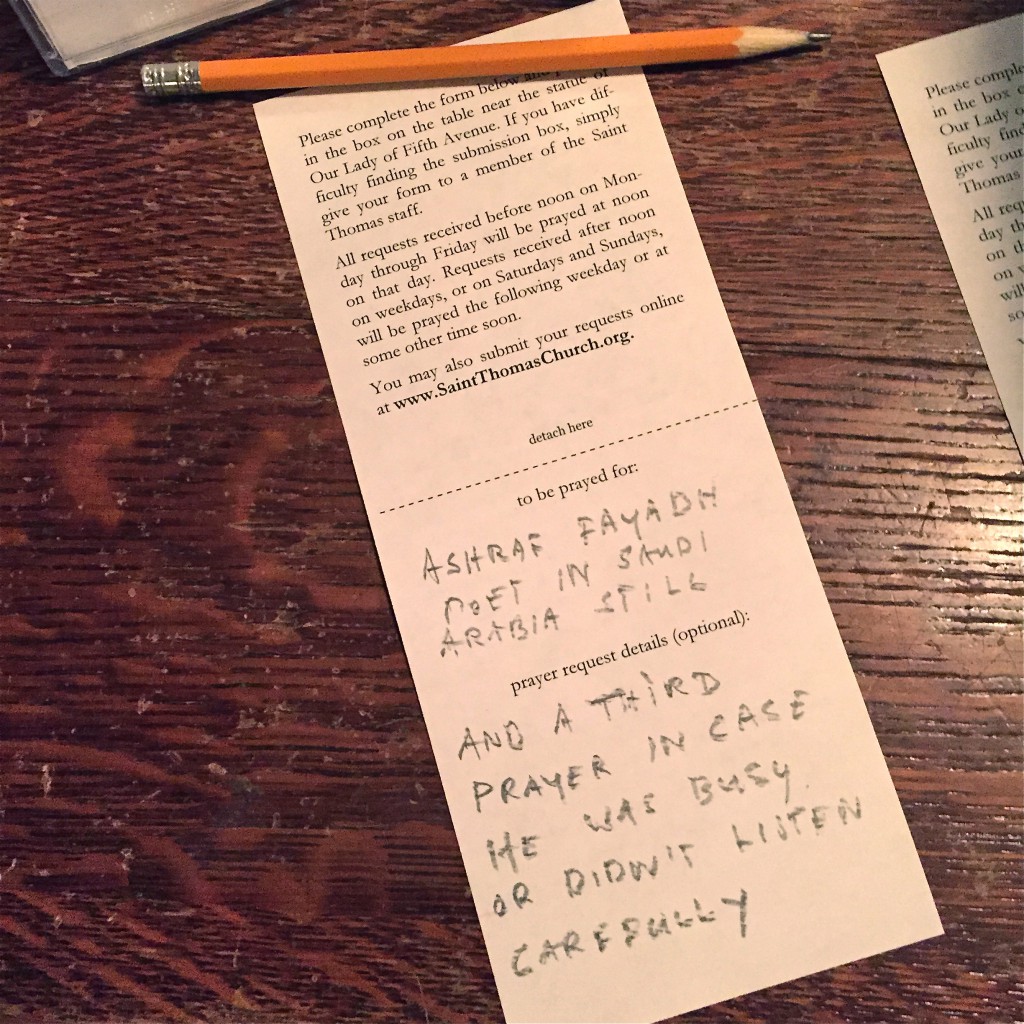

Two interviews in Arab News at the end of March 2015 with the Dutch ambassador in Riyadh made me think for a moment about His Netherlands Majesty’s amphibious warfare and command ship Johan de Witt, which carries these days a Swedish admiral in charge of a fleet close to the Yemen coast. Then I thought of an artist from Saudi Arabia, who decided that a will which soldiers are supposed to sign before they are off to war or peacekeeping, is something that you can frame, put on a wall and think about. To whom should a young soldier leave his furniture in case of his death and will he leave the cash in his back-pack to another than the guy who gets the furniture? It is something that art can do. Not necessarily to deny or confirm actions, but to add some or even the appropriate weight to them.

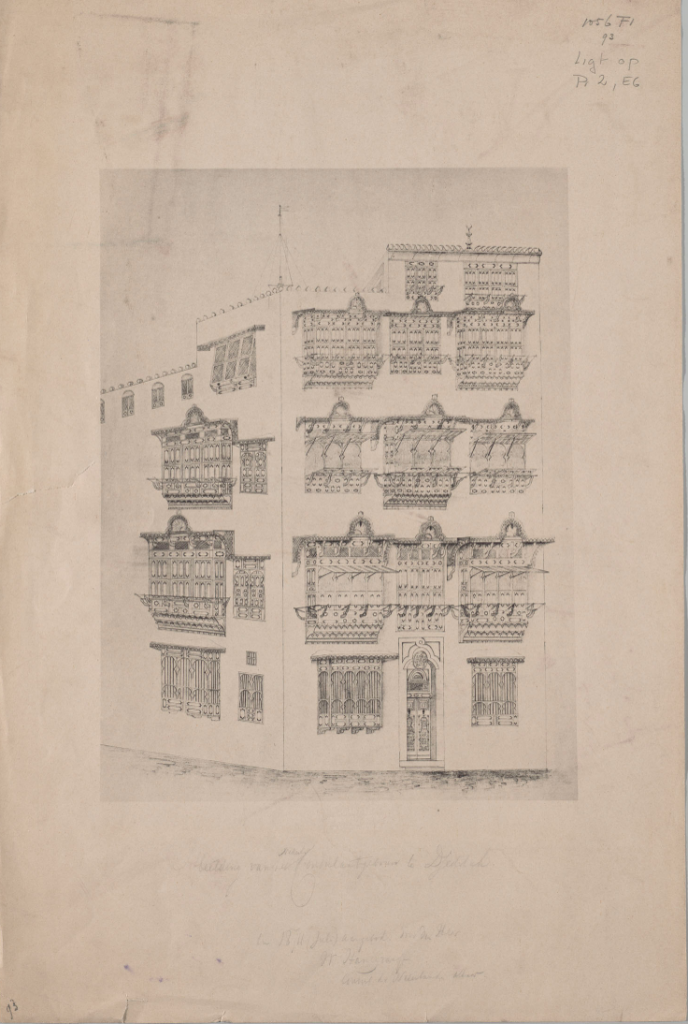

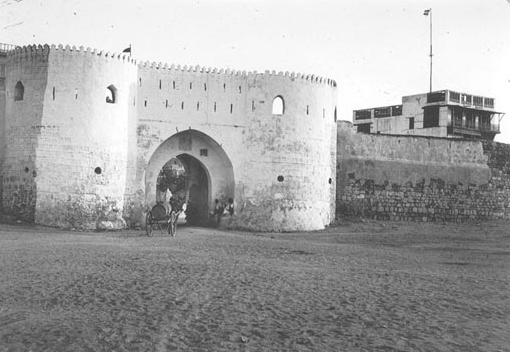

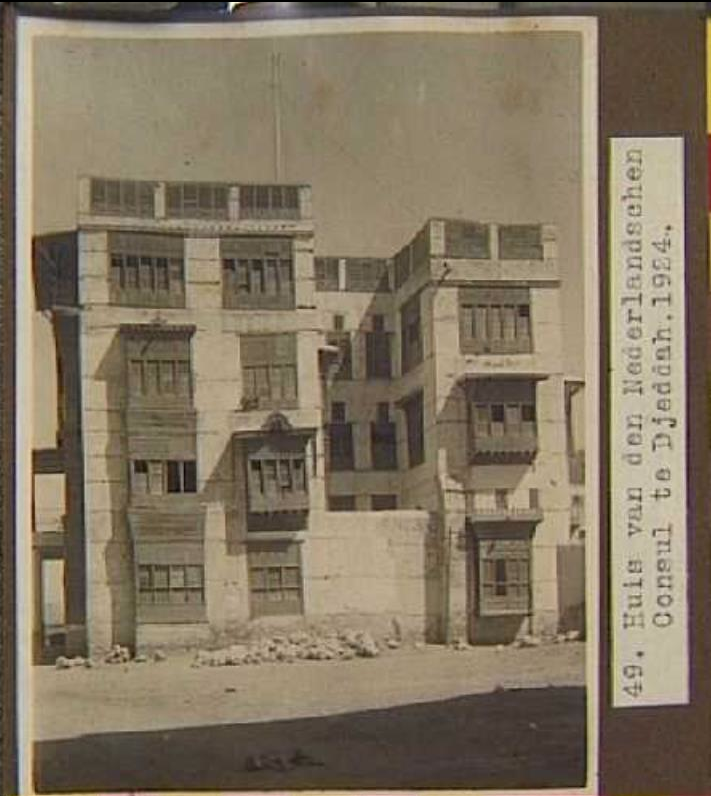

Then my attention turned to what the ambassador said about Dutch relations with Saudi Arabia: that they were established in 1872 with the opening of a consulate in Jeddah. He was twittering old pictures of the history rich Al-Balad district in search of the location of the old Dutch consulate and within a short period of time the combined effort of a few people in both Saudi Arabia and the Netherlands managed to dig up from digital sources a whole body of research on that. Something for a next blog. It turned my attention however not only to those heritage images of buildings, but to the question how the first generations in this kingdom, of the Netherlands, conceived and established relations with that other kingdom, in which lies Jeddah. I am in many ways a salafist and to be like that is what one learns at Leiden University law school: check the oldest and most authentic sources, when the truth needs to be a bit sharpened. And so I did and turned to the digitalized records of the States-General, the Dutch parliament, and the online historical newspaper website of our Royal Library in The Hague. Type ‘Djedda’ or ‘Mekka’ and their spelling varieties and see what the archives come up with about Dutch relations with the region, which is these days ruled by Al-Saud as not only regional kings, but also the universal custodians of two holy mosques.

![Wills of War, 2014, by and with Abdelkareem Qasem. At the [insert range here] exhibition in at Ather in Jeddah.](http://wordpress.aarnouthelb.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/04/IMG_1754-300x225.jpg)

Wills of War (2014) by and with Abdelkareem Qasem. At the [insert range here] exhibition at Athr Gallery in Jeddah.

Let me start with the conclusion of a little browsing and suggest for the beginning of relations an exact date that lies two decades earlier than the opening of the consulate in 1872. Ignoring even older trade relations with the Arabian peninsula, suggested by the Saudi embassy in The Hague, the date which carries most weight and consequence for the present is surely that of a decree by Governor-General A.J. Duymaer van Twist of May 3, 1852 to abolish a discouraging tax and fine on the pilgrimage to Makkah

[1]. At the time this event did not take place in Holland proper, but in the Netherlands East Indies, which is now the Republic of Indonesia. But it was nevertheless the result of legal developments in The Hague, where parliament in 1848 had adopted a constitution which unambiguously honored the freedom of religion. In the East Indies this constitution was translated into a Government Statute in 1854, but even before that the Supreme Court in the Netherlands East Indies ruled against the Makkah levy on formal grounds and the Governor-General subsequently abolished it. Muslims in the Indonesian archipelago then, wishing to connect with Makkah, were quick to profit from the new Dutch constitution and even quicker than Roman Catholics in the Netherlands wishing to connect with Rome – the Dutch were under Calvinist inspired rule and discriminated, joyfully I should add, against Catholics and their idols. A decision taken in Rome for example in 1853 to re-establish bishops in the Netherlands met with considerable more opposition than the decision to allow Muslims to travel to Makkah. So as a matter of interest: Dutch relations with Makkah are at least a year older than those with Rome.

It is the numbers that demonstrate the substance of those early relations. While in the years before 1852 only about 100 pilgrims travelled to Makkah every year, in the decade following the abolition of the levy 19422 pilgrims left for Makkah, while 11854 returned, creating no doubt beyond their personal experience, insofar they did not perish from disease or other dangers, not only increased learning and scholarship in Indonesia and in Holland, but also a group of Malay, Hadramaut Arab and Dutch citizens and businessmen in the Hedjaz.

Naturally, things don’t happen without debate. There were three issues to the debate, which did not precede, but followed the facts of 1852 and continued after the establishment of the consulate in 1872. First and most important were: concerns about the treatment of pilgrims in the Hedjaz, second were: how to differentiate between true and false hadjis and worries about their behaviour upon return, and third was, after plans developed for the Suez Canal: the opportunities for shipping and trade in the Red Sea, which was simply the choice for a consulate in Aden, Egypt or Djeddah.

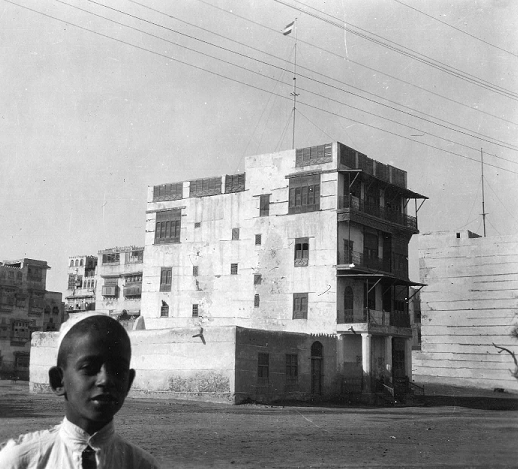

Arriving with pilgrims at Jeddah airport (2014).

What did the newspapers say about the returning pilgrims or hadjis? The first report about a returning hadji may be one in the North-Holland paper De Tijd of March 9, 1857 which discussed an article in the East Indies Society for Arts and Sciences magazine about a man named Kemas Mohamad Asahari [2], having returned from Makkah to his hometown of Palembang, who had bought a lithographic press in Singapore and established a first local or Indonesian printing office. The Quran which Asahari printed had received a positive review and the editors understood there was another such printer in the city of Surabaya. Referring to how printing enlightened Europe, the paper expressed high hopes for the population of the East Indies.

There were others who held a different opinion. Some members of a committee in parliament to review plans for the East Indies budget surplus of 1856 worried about zealots and their potential to disturb the peace. The government however again defended unequivocally the right of the majority of the population to fulfill their religious duty and refused to reinstate a fine and levy on the pilgrimage. The debate doesn’t end then and returns regularly with increased imperialist and racist behavior of the colonial authorities in the late 19th century and opposition to that from Muslims and other Indonesians, but the essence of freedom to move from the land for religious reasons was not abondoned by the Netherlands. Interestingly enough the goverment and journalists seem to have been more worried about those who had not really been to Makkah, but only left for Singapore and then returned and styled themselves falsely as hadjis to be exempt from work and have others listen to their presumed unsophisticated arguments as if these were holy knowledge. False promises of magical or sorcery-like events in Arabia too, were things that people needed to be protected of, is what one particularly critical contributor wrote to the Sumatra-courant (June 6, 1869). Aboel Fatiha was his name and he seems the only one to have ever spelled Makkah as ‘Makka’ and not ‘Mekka’ like Mecca in a Dutch East Indies newspaper, but might nevertheless have been a converted Arab siding with conservative Dutch friends.

The main issue however throughout the 1850s and 1860s seems to have been the welfare of ‘our’ pilgrims in terms of transport, hygiene, lodging, return tickets, diseases and treatment in the Hedjaz. This concern shows up as late as 1924, when the Dutch resident in Cairo, a former Governor-General of the East Indies, J.P. count van Limburg Stirum, seems happy in a letter to the foreign minister that Saudi forces under Ibn Saud had driven king Hussein out of the Hedjaz. Van Limburg Stirum believes Hussein was just another bandit robbing pilgrims on the roads to Makkah and expressed the hope that Ibn Saud would improve the treatment of pilgrims [3].

Saudi artists visiting Amsterdam after the Hadj exhibition in Leiden (2013).

When actually did the idea come up to establish a Dutch consulate in Djeddah? The papers show that another experienced and moderate nobleman may have been the first to suggest it. Herman Constantijn van der Wijck (1815-1889) had been the senior Dutch official in the city of Surabaja and must have had regular contact with the Arab community there. He ended his career in ‘Indonesia’ as a member of the Council of the East Indies. After returning to The Netherlands he wrote a brochure in 1865 – an appeal to the people of The Netherlands – in which, among other things, he proposed that the government fully support the pilgrimage to Makkah. He stated in his appeal that pilgrims should be given the greatest possible assistance without unnecessary formalities, that the government should appoint a trusted Arab as the Dutch consul in Djeddah and that it should grant the sharif of Makkah, or someone else of influence in the Hedjaz, a budget or reward to take into his care and protection pilgrims from the Dutch East Indies [4]. Inevitably someone wonders where in a hundred years the government will find a ‘trusted Arab,’ but such misanthropes do not take an inch of ground in reality.

In the Dutch parliament talk about a consulate in Djeddah shows up in October 1867 in the final paper of the committee to report on the budget for 1868. To cover shipping in the Red Sea, the government had proposed a consulate in Aden. Most members of the committee however, in view of the coming Suez canal, found that the consul-general in Alexandria should be made responsible for the Red Sea, while a minority opinion held that in the interest of pilgrims from the East Indies Djeddah was the most logical choice for a consulate. The government is not ready for that yet. But in 1870 it informs parliament that in September 1869 it had sent the navy’s screw propelled steamship Curaçao on a visit to show the Dutch flag in Persia, gather information in Djeddah and attend the opening of the Suez Canal. The Rotterdam paper NRC on July 13, 1869 however informs us that a person living in Djeddah, a certain M. Bourgarel, was awarded the distinguished knighthood of the Order of the Netherlands Lion. So apparently this man had already been taking care of Dutch interests in Djeddah. I discover mention of Bourgarel in Un Voyage A Djeddah, an 1864 travelogue, as a shipping agent for an Egyptian company and the chancellor of the French consul in Djeddah [5]. The traveller and writer also tells us of a walk with the British consul M. Stanley along the harbor or roadstead discussing the many ships that arrive from Batavia and Singapore with pilgrims from the Indies. Relations were clearly already there before the Dutch consul arrived.

It is in the 1872-1873 session of parliament that the minister for the East Indies, who contributes to the foreign minister’s budget for it, informs members that a consulate in Djeddah had indeed been established and that the appointed consul had arrived on his post. At that I will leave this short, done over an Eastern weekend, research into the beginnings of relations of the Netherlands and Saudi Arabia [6].

[1] The levy was 110 guilders and when it was not paid in advance it became a fine of 220 guilders upon return. The proceeds were used to finance local mosques in Indonesia.

[2] Hadji Mohammed Azhari is how his name is spelled in Schets van het eiland Sumatra (Amsterdam, 1867, p 75) by Pieter Johannes Veth. Resident De Brauw of Palembang had sent with some pride this printed Quran in 1855 to the Bataviaasch Genootschap. In the Tijdschrift voor Indische taal-, land- en volkenkunde, deel 6 (Batavia, 1857, p. 193). Kemas Hadji Mochammed Azhari from the kampung Pedatu’an is identified himself as the calligrapher on the last page of this Quran and he finished writing it on August 7, 1854). In an online Indonesian (Palembang Portal) source he is mentioned as Syeikh Muhammad Azhari al-Falimbani. From Pedatukan.

[3] J.P. Graaf van Limburg Stirum by Bob de Graaff and Elsbeth Locher-Scholten, Zwolle, 2007, p. 305

[4] Onze Koloniale Staatkunde. Een beroep op het Nederlandsche Volk, by Jhr. H.C. van der Wijck, The Hague, 1865, p. 79.

[5] In Nouvelle annales des voyages and by M. Le Dr. Daguillon, Paris 1866, p. 236

[6] Main sources: www.statengeneraaldigitaal.nl and www.delpher.nl.

![Wills of War, 2014, by and with Abdelkareem Qasem. At the [insert range here] exhibition in at Ather in Jeddah.](http://wordpress.aarnouthelb.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/04/IMG_1754-300x225.jpg)