Voor het eerst sinds de opening van het Bonnefantenmuseum in de jaren negentig, hield ik een dagje halt in Maastricht. Aan het Vrijthof werd me een kamer met balkon vergund met prachtig uitzicht op alles wat zich op en rond het vierde eeuwse graf van de immigrant Serbatios uit Armenië heeft verbeeld, opgebouwd en weer langzaam aan het verweren is. Het balkon leende zich voor baden in de september zon en nabladeren in de publicaties van de cultuurhuizen van Nederlands voorpost in Europa. De foto hieronder getuigt daarvan. De brochure van een tentoonstelling bij Marres, met hoofdletters Huis voor Hedendaagse Cultuur, wordt door mij opengehouden bij de humoristische verbeelding op een strand van het soort proeve van onthoofding, dat de laatste tijd vanuit de woestijn op internet met ons wordt gedeeld. Het zagend snijden zelf en de bloederige en pezige uitbraking van de hals worden daarbij niet in beeld gebracht. Dat is omdat op dat strand die gebeurtenissen niet werkelijk plaatsvonden – er is slechs in de foto een suggestie van onthoofding – en in de woestijn omdat het, zegt u het maar: amateurisch gebeurde door de Engelse rapper, door iemand anders werd uitgevoerd dan door die rapper, te wreed was om als propaganda materiaal te worden gebruikt of ook daar niet werkelijk heeft plaatsgevonden. Voor de kunst maken die verschillende oplossingen van een beeldpuzzel niet wezenlijk uit en voor het zekerstellen van de praktische waarheid heb je meestal een beetje tijd nodig. Ervaar vooral dat een verkeerde uitleg vaak vooraan in de rij staat voor snelle beslissers. Soms is dat de interpretatie die een journalist als Toine Huys er dezelfde avond aan geven moet met de insteek van een redacteur-stagaire.

Aan het Vrijthof met de brochure van The Unwritten in Marres

The Unwritten – over vergeten, zoekgeraakte en onvoltooide geschiedenis – is de titel van een tentoonstelling waarmee Valentijn Byvanck, de Hercules en het elfje van Marres, zijn eigen verleden tegelijk uitveegt en onderstreept. Hij ontworstelde eerder met kunst en de eeuwige frisheid van mode een museum aan zijn Zeeuwse klederdracht, maar deelde daarna in de monumentale uitglijder van het nationaal museum voor geschiedenis. Ik trof hem hier op straat, in zijn verbanningsoord misschien, bij toeval en een goed toeval was dat. Het bracht me ertoe aan het einde van de dag, na bezoeken aan de beide basilieken en het Bonnefantenmuseum, het Maastrichtse huis voor eigentijdse cultuur te bezoeken en een zinnige, tegelijk gevarieerde en coherente tentoonstelling te zien en onbestemde gevoelens te ontwikkelen over de verschillende huizen waarin mensen met een verbeelding, die individueel en autonoom is, kunnen stoeien.

De strandfoto is overigens een moment uit Return to Adriaport, een imaginaire, enigszins historische, documentaire of reeks van beweegplaatjes – de badgasten staan stil, de golven klotsen – over de manier waarop ‘landlocked’ Tsjechoslowakije eens meende met een tunnel naar de Adriatische zee en daarin een bewaakt eiland, opgeworpen met de uitgegraven aarde van de tunnel, zijn bevolking een gecontroleerde illusie van strand, zee en vrijheid te kunnen bieden. Zulke oplossingen voor vrijheid bestaan slechts tijdelijk, dacht ik, genietend van de mooie en ironische zwart-wit beelden op een geheel witte zolderkamer, nog aarzelend of ik deze projectie van Adela Babanova (Tjechoslowakije, 1980) de verweldiger van de Krim moest voorhouden of die Saoedische krachten die buiten de grenzen van het eigen domein de culturele expressie van landgenoten beijveren te begeleiden. A propos: een geheel witte kamer betekent dat ook de vloer wit is. En dat werkt. De kamer wordt zo een universum.

Sint Jan in disco. 15e eeuwse decoratieve schotel met de verbeelding van het afgehouwen hoofd van Johannes de Doper. Schatkamer Sint Servaasbasiliek.

‘Wij willen meer zijn dan een museum. Heeft u dat zo ervaren?’ stond er boven het register voor bezoekerscommentaar bij de uitgang van de Schatkamer van de Sint Servaasbasiliek, waarschijnlijk de oudste kunstcollectie van Nederland. Tussen 800 tot 1800 werd in de schatkamer gedurende bijna duizend jaar een zilveren triomfboog bewaard, waarop als symbool van vrede een kruis overeind stond, totdat het Karolingische kunstwerk voor de zilverwaarde werd omgesmolten. Die kennis voerde mijn gedachten even naar de spullen die Rotterdam van de hand doet om het salaris van de directie en medewerkers van het Wereldmuseum veilig te stellen. Berg de collectie liever op en toon ze eens in de vier jaar ‘in heiligheid’ in de Kunsthal aan alle in Afrika gewortelde burgers van die koophandelsstad onderaan de Maas. En voer ze eerst in processie door de stad. Zo ging het vroeger in Maastricht en het scheelt wat folders en reclame.

Waarom eigenlijk wil de schatkamer ‘meer zijn dan museum?’ En op wat voor manier? Is er iets mis met de kunst- en geschiedenismusea? Er is aanleiding om dat te denken. De voorzitter van de museumvereniging drukte mij laatst een boekje in handen: Meer dan waard, over de maatschappelijke betekenis van musea. Maar met bijdragen van Jeroen Branderhorst van de Bankgiro Loterij. En met paragrafen over economische, belevings- en educatieve waarde, maar geen enkele expliciet over een ‘meer dan waard’ beschavingswaarde. Mij is dat een te innige omhelzing van museum en aflatenhandel. Een directeur van Volkenkunde vroeg ik op een vriendenvergadering, nadat hij een tentoonstelling van zwaarden voor kinderen opperde, of hij geloofde in zijn museum? Hij keek alsof hij braambossen branden zag. Daarom pakte ik na mijn bezoek aan Maastricht de telefoon, sprak met de koster van de basiliek en op zijn suggestie met de voorzitter van de Stichting Schatkamer Sint Servaas. Die voorzitter legde mij het ‘meer zijn’ zo uit:

‘In een museum kan je van alles exposeren, zoals auto’s en luciferdoosjes. Maar de liturgische voorwerpen en reliekhouders hebben echt meer te betekenen dan wereldse voorwerpen. Wij willen dat de opvattingen die onze voorouders hadden over de manier waarop je met zulke voorwerpen omgaat bij het publiek overkomen. Er moet toch meer zijn op aarde dan een waardevol schilderij of andere kunst, tussen haakjes, voorwerpen.’

Hij heeft wel gelijk, maar waarom eigenlijk? Omdat wij ons de barbaarsheid moeten herinneren die Sint Jan ten deel viel misschien. Wat te denken van de gouden sloep, de keizerlijke serviezen uit Sint-Petersburg en kleurige, onzinnig nieuwe totempalen? Wat vertellen die de mensen. De sloep die werd gemaakt in de geest van Marie Antoinette, ook onthoofd overigens, tetterde het op mijn autoradio op weg naar Maastricht: moet weer varen. Het goud wordt gepoetst, de mensen moeten komen kijken. De brandmanagers van de Bankgiro Loterij drammen al een tijdje, met een subsidie van een miljoen, dat onze verstandige familie Van Oranje-Nassau de boot in moet, die al tweemaal door hen op de wal werd gezet. Door koning Willem I voor een moderne stomer en door koningin Juliana voor hedendaagse soberheid. Dat is waaraan het Scheepvaartmuseum ons hoort te herinneren.

Margret (1960-1970) uit de koffer van Günter K. bij Marres.

Aardiger, vreemder dan de Rijksmusea, die soms dus kitsch en kietel venten – het Rijksmuseum kocht een paar jaar geleden met geld en invloed van de loterij twee gouden huwelijkskoffers uit de Versaille-cultuur – was het zeer persoonlijke museumpje dat door iemand werd gevonden in een koffer en bij Marres wordt tentoongesteld onder de naam Margret. Het is een collectie van foto’s, documenten en spulletjes, die getuigt van een geheime relatie van 1960 tot 1970 en gevonden werd in een boedel van een overleden Keulse zakenman. Het werd door een galeriehouder herkend als verontrustend en tentoonstellingswaardig. Een erfgenaam ontbrak en een integere boedelafwikkelaar misschien ook. De vrouw was in het begin van de relatie 24 jaar oud en vast hangt hier nu iemands grootmoeder ongevraagd in soms haar schaamhaar tonend pikante blootje. Fascinerend wel, ergerlijk ook. Een beetje bovendien zoals het tentoongesteld gebit van een heilige. Maar objecten proberen althans bewijs te zijn van een vertel-waardige waarheid.

De voorzitter van de schatkamer bedoelde vast alleen de doosjes waaruit lucifer ontsnappen kan, niet die waarin lucifer voorgoed geborgen is. Er is kennelijk volgens hem iets aan de hand met de kwaliteit van de voorwerpen die men bewaart in een museum en vreemd genoeg staat juist daarover niets in de voorwaarden voor museumregistratie, de museumnorm, het kwaliteitskeurmerk voor musea. Die norm faalt eigenlijk in zijn hoofdzaak. Je kunt een luciferdoosjesmuseum of blootfotootjesmuseum registreren, als de klimaatbeheersing maar in orde is en de bestuursstructuur lijkt op die van instellingen met aandeelhouders. Wat wij museaal behandelen moeten, is de werkelijke kwaliteitsbeslissing, en die lijkt tegenwoordig uitbesteed aan geldwisselaars. ‘Als u bereid bent te investeren, is veel mogelijk,’ zei een fondsenwerver van een Rijksmuseum me vandaag, toen ik informeerde naar de achtergronden van het opheffen van de zoveelste noodlijdende vereniging van museumvrienden.

Dat een almachtige alleen de verzameling van de schatkamer zou hebben aangeraakt, en niet soms ook die van wereldse voorwerpen. Met die gedachte doe je juist een almachtige tekort, denk ik. En ook de kunstenaar Jonas Staal, die meent dat de kunst zich niet in een eigen domein moet of zelfs kan terugtrekken. Of meent de lezer dat de scheiding van kunst en staat juist wel een goed idee is? Waarom financiert de staat wel ongrijpbare kunst en niet het dak van de Westermoskee? Waarom hoeven kunsthuizen zich niet als een kerk op eigen kosten zelf te verheffen? Zo gaat dat wel in Saoedi-Arabië, waar de staat juist de moskee financiert en verzamelaars de beeldende kunst. Vragen die in Marres opkomen.

Nefandus (2013) van Carlos Motta bij Marres.

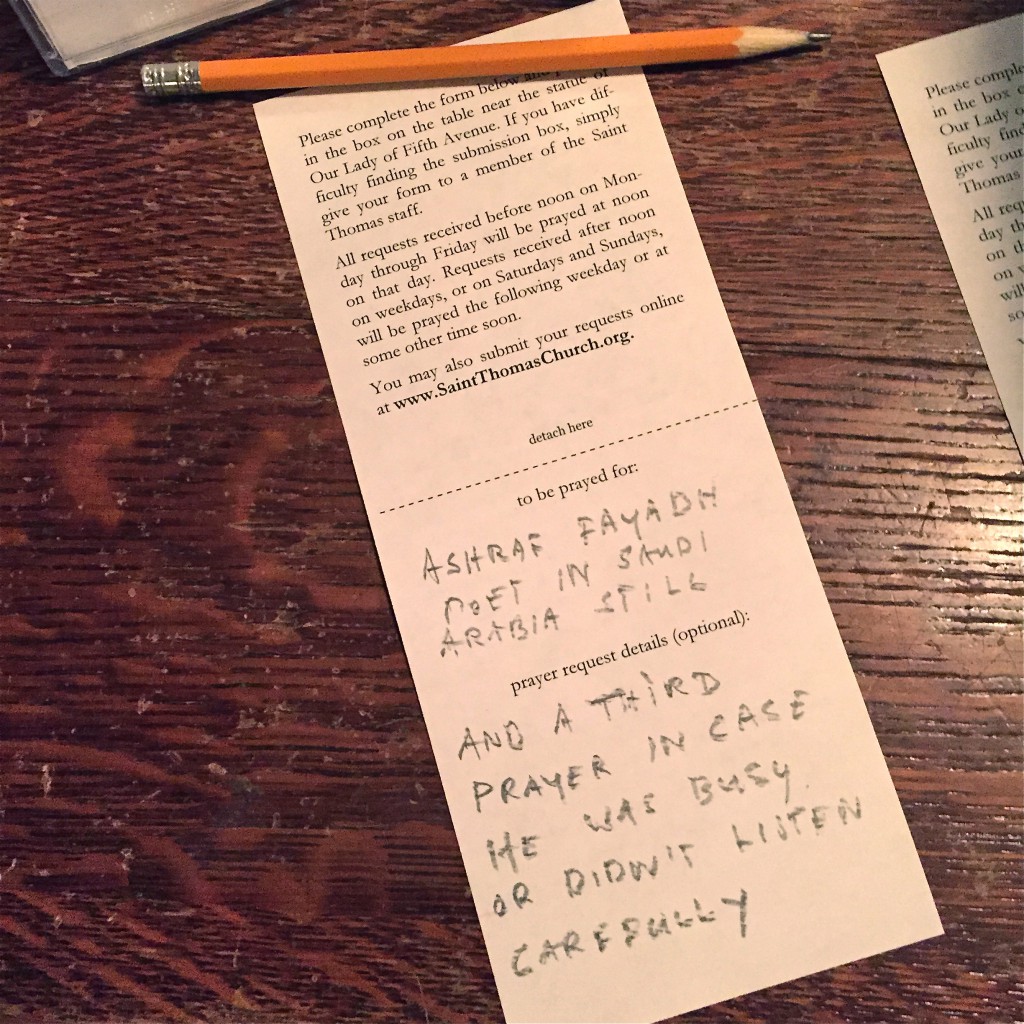

Nefandus was mijn lievelingswerk bij Marres. De kunstenaar Carlos Motta (Colombia, 1978) confronteert in een dertien minuten durende video een geschiedenis uit een miezerige 16e eeuwse gravure van de Luikse Theodoor de Bry met de rustige immensheid van een Latijns-Amerikaans landschap rond een kalm stromende en ondiepe rivier. Daarin beweegt een man op een kano of boomstam zich langzaam voort terwijl een Spaanse stem en één die spreekt in de taal van de Kogi (Jaguar) samenleving, de ondergang van een geschiedenis beschrijven, die werd gekannibaliseerd door die van de Luikenaar; in wezen een journalist die verhalen in een tweede hand doorgaf aan publiek dat hem daarvoor betaalde. De ijzersterke tekst met een tempo dat onmiddellijke contemplatie toestaat, beweegt zich over de onmogelijkheid van registratie van geschiedenis, zowel in de betekenis van onduldbaar als die van niet-realiseerbaar, en knoopt dat op aan de slachtig van ‘sodomieten’ in de prent van De Bry en het veronderstelde normale voorkomen of de viering van homosexualiteit in precolumbiaans America. Of dat laatste werkelijkheid is of de gewenste geschiedenis van de in New York wonende en werkende kunstenaar, is mij en hem kennelijk nog even een vraag. Dat mensen overigens zo verschillend kunnen zijn als de Kogi spreker in de eerste regels van het volgende suggereert, betwijfel ik: ‘their vice was our saintliness, their nightmare our dream, their monsters our idols, their perversions our beliefs, their history our calvary, our land their treasure. Nog een zin: ‘things turned into history and named against traditions, farce disguised as truth.’ Hoe hebben de Franken in Limburg die Oosterse bisschop ervaren, vroeg ik me af. Of de Bantoes in Zuid-Afrika de geschiedenis volgens een Amsterdamse winkelierszoon?

Hendrik Verwoerd in Boys (2004) van Annie Kevans.

Poetin ontbrak nog in Boys van Annie Kevans (Frankrijk, 1972), een reeks van negenentwintig kinderportretten van despoten, die wat mij betreft bij eigenaar Saatchi Gallery had mogen blijven. Natuurlijk, kinderportretten van lieden als Hitler Senior – dichter en uitgever Jaeggi zond me ooit een boek van Mulisch over de zoon-, Jorge Videla en Pol Pot leveren een boeiend contrast van schuld en onschuld en mogelijk alternatieve geschiedenissen, maar de middelmatige studies die Kevans van hun gezichtjes maakte en het volledig ontbreken van verdere elaboratie van het eenvoudige concept, stond me tegen. Wel was er zondige trots over de stevige bijdrage van het Koninkrijk der Nederlanden aan de reeks. Met de voorlieden van apartheid en corruptie, Verwoerd en Suharto. Het kwaad: dat zijn de kleuters van een Amsterdamse winkelier en zijn gemangelde leverancier van koffie en suiker. De makelaar Droogstoppel verbond hun vaders met transacties.

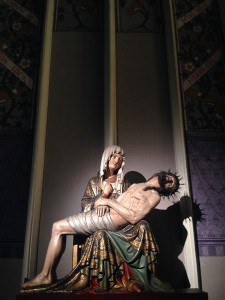

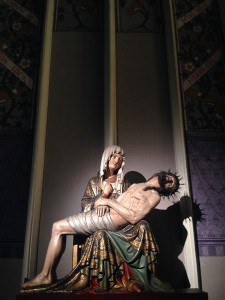

In een kapel van de Servaasbasiliek omhoog kijken naar een polychrome Pietà of bij Marres naar de video Re/trato van Óscar Muños (Colombia, 1951). De donkere kamer, liefst met een goede zitplaats, waarin tien tot vijfentwintig minuten aandacht kan worden gegeven aan een enkele film of video, met ruime mogelijkheden voor beelden, contemplatieve stilte en tekst, ervaar ik als het meest bevredigend. Kunstpausjes schrijven echter te vaak jargon. Marres suggereert dat de kunstenaar ‘het vermogen onderzoekt van beelden om herinneringen vast te houden.’ Misschien, maar kijk. De kunstenaar stelt en toont in de casus aan dat die beelden juist snel verdwijnen en steeds opnieuw en iets anders gepenseeld kunnen, moeten of zullen worden. Hoeveel Pietàs zijn er in de loop van de eeuwen door beeldenmakers wel niet gemaakt? Daarbij geven die steeds de mogelijkheid tot enige heruitvinding. Getuig, dacht ik, met Maria en Muños: een jihadi als Jezus, die geen moorden pleegt, kan ook martelaar worden.

Pietà in de Sint Servaasbasiliek.

Re/trato (2004) van Oscar Muños in marres.

In de stralende zon de brug over en gewandeld naar het Bonnefantenmuseum. Van dat museum aan de Maas wilde ik formule en het gebouw beter begrijpen, maar door de Eisensteinse trappen en twee Brabantse engelen uit de collectie Neutelings, veel overtuigender heilig dan een vrouwenbeeld van de Limburgse snijder Steffenswert, begreep ik alles al. Dit is een gebouw ontworpen om een museum te zijn en niet een gothisch stripverhaal, zoals het Limburgse museum in Amsterdam. Zelfs een man genoemd ‘God’ zetelt hier op een plankje aan de muur en niet in de gevel zelf. Het beeld van de engelen blijft in mijn geest hangen en later bedenk ik dat het monniken zijn, die zijn afgebeeld als engelen. Het is vast de ijdelheid van kerkheren in de kunst, die de reformatie soms al aankondigde. Maken wij nu iets dat aanwijsbaar binnenkort onder een ikonenslag terecht zal komen?

God op een plankje in het Bonnefantenmuseum.

Wat haal je eruit als je door een museum dwaalt? Misschien dat ik ooit zoveel vroege Italiaanse werken heb gezien in Florence en Sienna dat de verzameling hier aanvoelt als een onbeholpen kunsthistorische oefening uit de 19e eeuw. Onverwacht is een heilige dame van Pietro Nelli (Italië, ca 1365) in roze, die het in de Pinky ijswinkels in de binnenstad niet slecht zou doen. Hoe eigentijds zijn altijd weer de oudste dingen. En nieuw voor me is de schilder Alexander Keirinck (Antwerpen, 1600) van wie hier een eenvoudig, maar prachtig bosgezicht hangt met vaag een enkele wandelaar. De tweede verdieping is toegewijd aan de hedendaagse kunst. Ik film zeventien seconden lang de projector die Marcel Broodthaers (België, 1924) in die tijd drie seconden eeuwigheid werpt. In zijn stijl was er een tentoonstelling van nuttige knutselobjecten, noem ik ze maar, gemaakt door mensen rond Maastricht, gevonden en verzameld door Vladimir Arkhipov (Rusland, 1961). Ik noem er een paar: kalverhut, zandslurven-vulwerktuig, anti-reiger koepel, laarzendroger, carnavalsfiets, hockeystick-bezem, kruiwagen met twee wielen, boetseerbok, enzovoort. Soms waren de objecten zelfs mooi, zoals de plank met spijker-sorteerflessen en de breinaaldenmap. Dat dingen knutselen soms nieuwe woorden maakt, vond ik de aardigste gewaarwording. En misschien een inzicht in de oervorm, het oorspronkelijke bestaansrecht, van creativiteit. Waarom is het dat we engelen mooi maken en kruiwagens niet?

Breinaaldenmap (2012) van Christine van Leeuwen, gevonden door Vladimir Arkhipov in 2014.

Ik sta even stil bij een apostel met een heilige tekst en een zwaard. Zijn attributen vormen ook de vlag van Saoedi-Arabië, zo verschillend zijn we niet. Het beeldje in het Bonnefantenmuseum is een bruikleen uit Aken (ca. 1350-1375). Het moet de projectie van een Frankische kruisvaarder zijn, denk ik. Zwaarden waren er niet in de oudere schatkamer van de Sint-Servaasbasiliek. Wel in die heilige schatkamer van het Topkapi Paleis in Istanbul, in welke stad ik één dag was en ontwaakte met een bericht in de International Herald Tribune over een onhandige speech van een paus in Regensburg en de boosheid van Turkije. Nederland hanteert slechts bij inhuldigingen van de vorst het enkelvoudige rijkszwaard – en verder veel F16’s – maar in Istanbul stelt de regering van het voormalig kalifaat als heilige schat de zwaarden van de profeet en zijn metgezellen tentoon naast overigens de brief met de vermeende zegel van Mohammed, die ISIS nu gebruikt op zijn vlag. Dat alles geniet voortdurend toezicht van een imam die de Koran reciteert. Meer dan museum zijn, kan kennelijk ook betekenen dat je objecten met rituëlen van eerbied en zwijgen omringt. Veel wetenschappelijk onderzoek vindt er in het Topkapi paleis niet plaats, hoor ik. Juist dat is misschien een gebrek aan eerbied. Of getuigt het ‘unwritten’ laten van echte geschiedenissen van een zeker geloof in de werking van kunst?

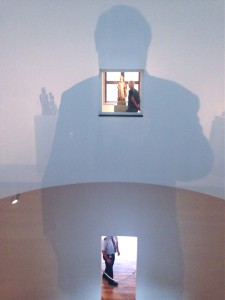

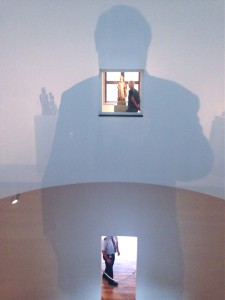

Beelden ontstaan ook toevallig, zoals een zelfportret veroorzaakt door mijn schaduw toen ik door één van de raampjes van de cylinder in het voorste deel van het museum van archirect Aldo Rossi een foto maakte.

Toevallig zelfportret met Aldo Rossi.

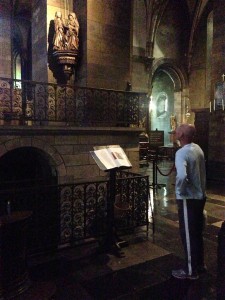

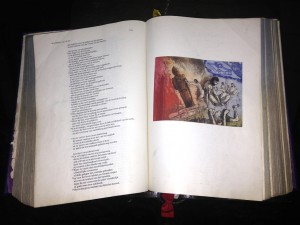

De objecten die Arkhipov verzamelde en hopelijk toevallige zelfportretten, zullen vast gevrijwaard blijven van de toorn van de bijbelbaas van de Onze Lieve Vrouw “Sterre der Zee” basiliek. Die liet voor een beeldengroepje in de donkere basiliek een bijbel open liggen op de pagina met een gekleurde ets van een beeldenstorm, gemaakt door illustrator Marcus van Loopik (1950), bij een tekst over de oorsprong van afgodsbeelden (Wijsheid 14, 12-21), die ik zoals veel van dat boek niet kende. Ik zal de passage binnenkort eens nader bestuderen. De oorsprong begrijpen van de dingen, gaat aan het verbod of de toelating kennelijk vooraf. Dat is ook een inzicht voor museumbestuurders.

In de OLV basiliek.

De oorsprong van afgodsbeelden met illustratie van Marcus van Loopik in de OLV basiliek.

Ter afsluiting een zaakje van beeldenzwendel. Op de ochtend van mijn vertrek wilde ik naar de Matthiaskerk omdat zich daar uit het hitte van het gevecht om de onafhankelijkheid van de zeven verenigde provinciën een grafmonumentje bevindt voor een Spaanse officier die is gesneuveld in de wrede tunneloorlog, gelijk die van Gaza, die een belegering van Maastricht in 1579 is geweest. Ik trof echter aan de andere zijde van de kerk nog een later graf. Dat van een Franse Luitenant-Generaal in Staatse dienst met de op Marres gelijkende naam Demarets, die in 1792 aan ouderdom is overleden. In twee kwartieren van zijn wapen komen de drie meerbladeren voor, die ook het logo van het Huis voor Hedendaagse Kunst Marres vormen. Enig speurwerk leerde me dat de Limburgse bierbrouwers van wie dat huis ooit zou zijn geweest hun afstamming en dus het beeldgebruik van dat logo slechts met ongeschreven geschiedenis waar kunnen maken. In een museum leer je wellicht of je dat geloven wilt of kunt. Echt is in ieder geval dit: een foto die ik maakte van een Piëta en de hoedenwinkel Sheer Elegance in een straat in Maastricht aan het einde van mijn dag in die stad.

Graf van Demarets in de Sint Matthiaskerk in Maastricht met twee kwartieren met drie meerbladeren.

Maastricht, 16 september 2014.

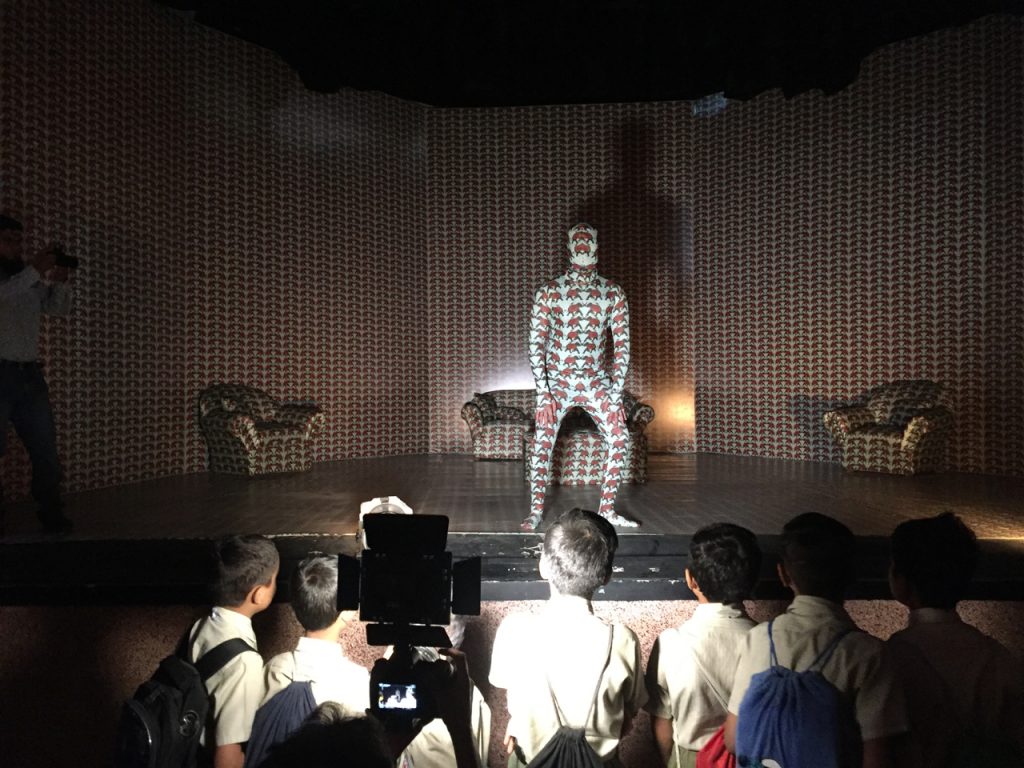

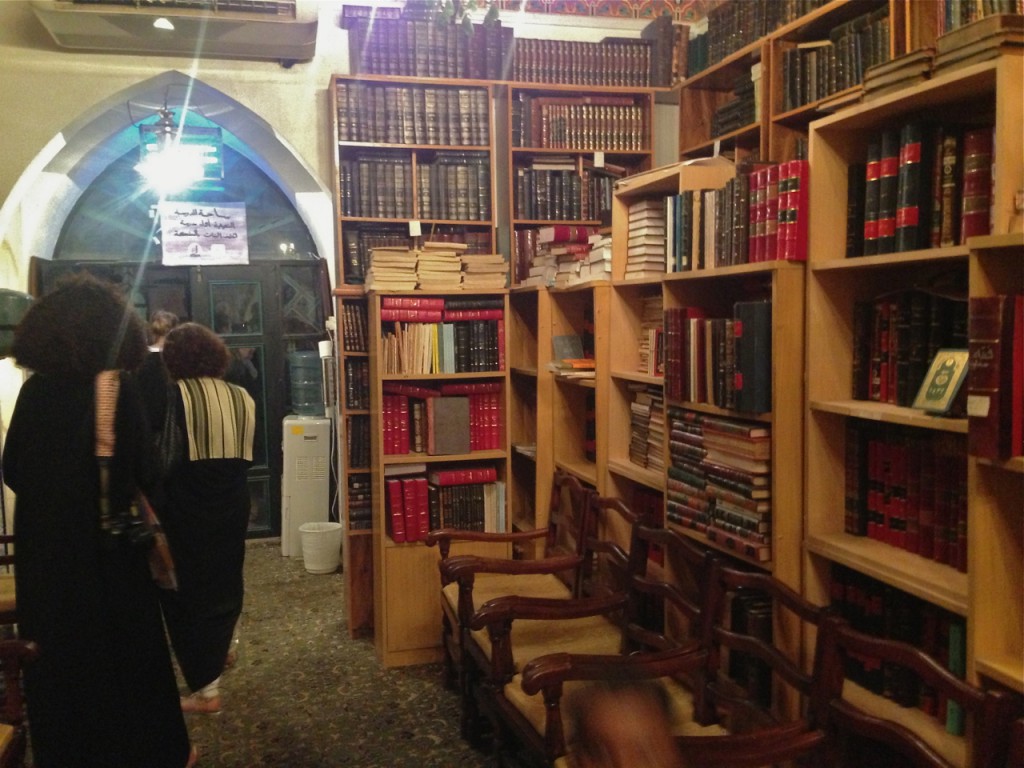

![Wills of War, 2014, by and with Abdelkareem Qasem. At the [insert range here] exhibition in at Ather in Jeddah.](http://wordpress.aarnouthelb.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/04/IMG_1754-300x225.jpg)